Policy Brief & Legislative Recommendations

The Future of Behavioral Health Services for Youth with Foster Care Experience

Emma Buckland Young, Angelique Day, Charles E. Lewis, Jr., Rebecca Louve Yao

Emma Buckland Young is a student research assistant at the University of Washington. Angelique Day, PhD, MSW, is an associate professor at the University of Washington. Charles E. Lewis, Jr, PhD, MSW, is the director of the Congressional Research Institute for Social Work and Policy (CRISP). Rebecca Louve Yao, MSW, LCSW, is the executive director of the National Foster Youth Institute.

Summary:

More than 390,000 children are in the U.S. foster care system,1 not including former foster youth who have aged out but still receive governmental support. Youth with foster care experience (FCE) are up to 62 percent more likely to face mental health challenges, including depression,anxiety, and PTSD, than their peers in the general population.2 Hence, access to effective therapy is vital. However, most of these youth are insured through Medicaid, 3 which constrains access to a wide array of mental health treatments and primarily covers only traditional “talk therapy” modalities. Youth with FCE have expressed that talk therapy modalities are not universally effective and leave many youth in need of better support. Alternative treatments such as art therapy, movement therapy, music therapy, and equine-assisted psychotherapy – already available to higher-income populations – show promise in treating mental health conditions often faced by youth with FCE and so offer the potential to fill this gap. However, as of now, there is no clear agreement between or guidance offered to states on whether alternative therapies are covered by Medicaid. In order to achieve equitable access to mental health care, we must ensure that foster youth have the ability to choose from a wide array of mental health treatments, including alternative therapies. Equitable access necessitates coverage and reimbursement under Medicaid..

To achieve this goal, the federal government should fund a five-year minimum

demonstration project that will:

- Develop an evidence base for the success of alternative treatments with youth with FCE,

- Establish guidance for states, tribes, and territories on best practices to reduce and eliminate access barriers for these treatments,and

- Propose policies and procedures to support braided funding mechanisms and billing codes through Medicaid and Title IV-E to ensure full reimbursement of the actual cost of covered therapies for foster youth.

The State of Mental Health Among Youth with FCE:

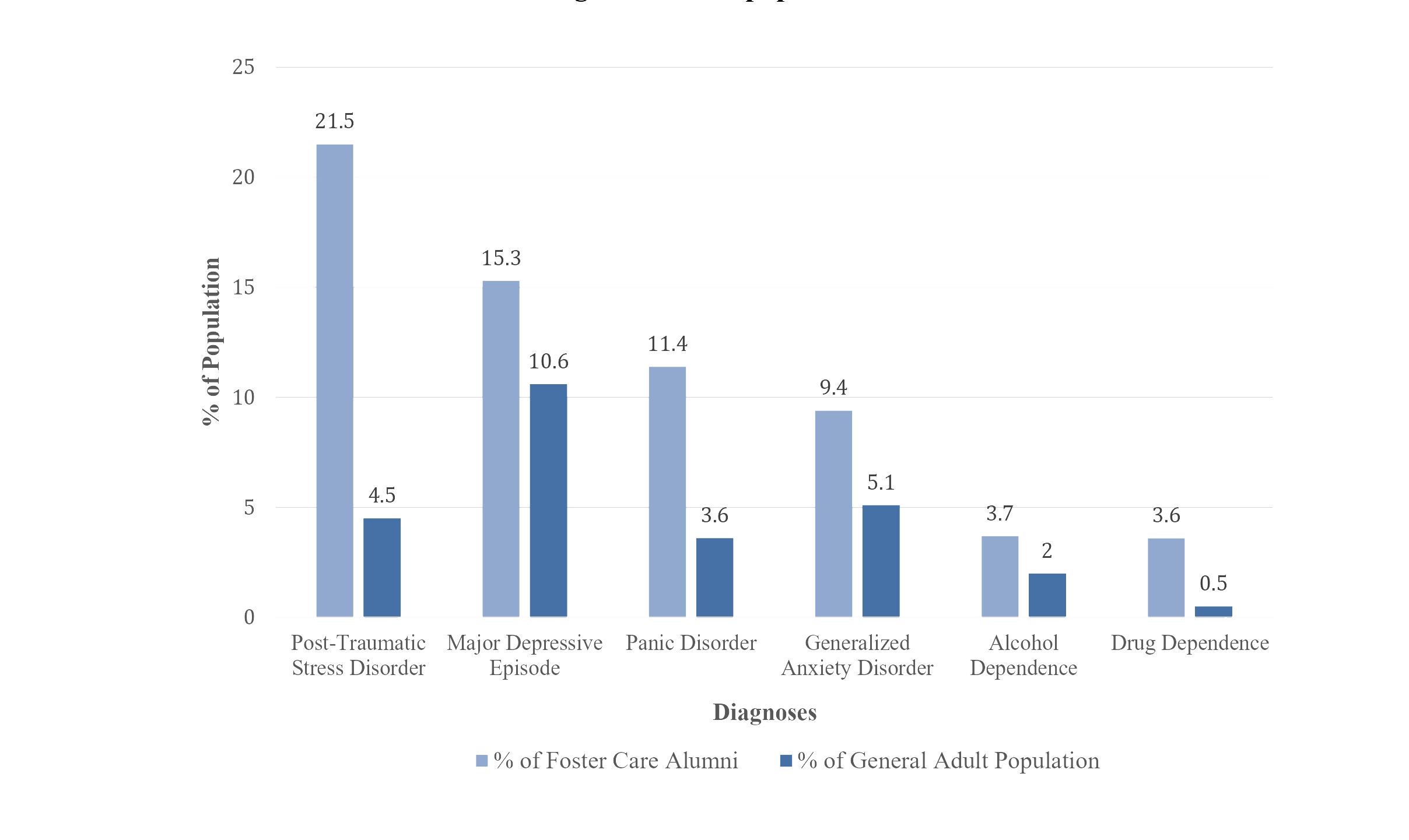

Research consistently shows that youth with FCE face significantly higher rates of mental health challenges than their peers in the general population. More than half of adolescents in the child welfare system have been diagnosed with at least one mental health disorder, compared with just one-fifth of adolescents in the general population.4 Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) represents one of the most significant disparities: researchers found that 21.5 percent of the former foster youth population were diagnosed with PTSD, compared to only 4.5 percent of the general adult population.5 (See Figure 1.)Rates of PTSD among former foster youth exceeded even those for U.S. war veterans.6 Other mental health conditions, including depression,anxiety, conduct disorder, and panic disorder, were also found to disproportionately impact youth with FCE at significant rates. 7 (See Figure 1.) Youth with FCE are more likely to have experienced child maltreatment and trauma, which is a “significant risk factor” for PTSD, anxiety, and depression, among other illnesses.8 In 2020, 63 percent of children entering foster care did so

under circumstances of neglect, 12 percent because of physical abuse, and 4 percent because of sexual abuse. 9 Entering foster care can itself cause stress, grief, confusion, and trauma,10 and it does not end with removal from their home – placement instability puts youth at higher risk for negative psychiatric and mental health outcomes, 11 and youth in outof-home placement may also face a greater risk of physical and sexual abuse than the general population. Untreated mental health issues put individuals with FCE at a higher risk of poverty14 and unemployment15 – each year in the U.S., serious mental illness is associated with a loss of $193.2 billion in earnings.16 Individuals with untreated mental illness are also more likely to experience homelessness,17 school dropout,18 substance use, 19 and incarceration,20 all of which impose high costs on society.21 The risk of these outcomes is even higher for people of color,22 who make up a disproportionately large segment of youth with FCE.23 As a result, youth and society alike suffer the consequences of inequitable mental health services.

The Barriers to Mental Health Treatment for Youth with FCE

Medicaid & Mental Health

Medicaid is the sole insurance option for most youth with FCE, the vast majority of whom are neither eligible for nor able to afford other insurance plans.24 Medicaid covers youth up to age 21 who are in out-ofhome placement or are receiving adoption support, and youth up to age 26 who were enrolled in Medicaid when they aged out of foster care.

Especially for those reliant on Medicaid, the U.S. mental healthcare system is “overburdened and underperforming.”26 There are three major barriers preventing youth with FCE from receiving effective mental health treatment: service availability, service accessibility, and quality of care.

1. Service availability: There are far fewer therapists for youth than are needed. Current estimates suggest that this shortage will only get worse: according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, there will be 10,000 fewer mental health professionals than needed by 2025.

2. Service accessibility: Very few providers accept Medicaid. Because Medicaid provides

low reimbursement compared to other insurance and entails significant administrative burdens (including battles over reimbursement and funding coordination gaps between agencies),providers are often unwilling to treat Medicaid patients.28 Unless youth with FCE can pay high patient costs out of pocket, theiroptions are limited. This primarily affects former foster youth who often face a “service cliff” when they age out of care and no longer receive child welfare-provided medical benefits.29 Medicaid coverage of alternative therapies also varies widely by state. For those states where some alternative therapies are covered, coverage is often restricted to specific populations (e.g. those who have been diagnosed with developmental disabilities).30 These inconsistencies add complexity and further hinder youth’s attempts to access mental healthcare.

Talk Therapy is Not Always the Right Treatment

Currently, Medicaid covers behavioral health treatments that employ “talk therapy” as the primary modality of service: evidence-based practices such as cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, and other modalities that focus on discussiondriven solutions.32 In recent years, however, there has been increasing recognition by researchers and youth that talk therapy is not a universal solution to mental health challenges.

Trauma and neglect can impact brain development and lead to delays in language acquisition,33 which may decrease the capacities and willingness of youth to participate in traditional talk therapies. Young children may struggle to understand abstract emotional constructs through talk therapy, while adolescents, who are often referred to therapy by an authority figure, may be resistant to treatment they view as unnecessary.34 In addition, completion rates for youth in talk therapy are very low35 – one study found that more than a quarter of youth with FCE dropped out of therapy within three months, 36 and foster youth report that, when they are in therapy, inconsistent and infrequent treatment is common. 37 Research suggests that a minimum of 11 to 13 sessions are necessary for most patients to improve38 – a threshold that does not appear to be met for foster youth.

Research also suggests that trauma, especially early trauma, imprints itself in neural pathways and on the body – that trauma is experienced and stored in nonverbal parts of the brain that override verbal processes.39 Hence, talking alone may not be enough to address the trauma, and nonverbal therapies may provide a path to healing that verbal therapies do not.40 Though talk therapy may be an effective model for some youth with FCE, others may find that it does not successfully address their problems.

In August of 2021, the National Foster Youth Institute (NFYI) convened nearly fifty youth with FCE for a listening session to learn how to support them better. At the session, participants described the barriers mentioned above, including the insufficient number of accessible therapists and the impact of inconsistent treatments. Participants also remarked that the environment of talk therapy could make it difficult to open up and to feel safe and stable.

Youth with FCE present at the session also expressed interest in alternative therapeutic treatments that they felt would be better suited to their needs and comfort levels.42 Youth suggested that they would be more likely to engage in and complete therapy if they were able to choose between multiple treatment options.43 As discussed below, evidence shows that alternative therapies discussed at the listening session are linked to positive outcomes.

Proposed Alternative Treatments

Many youth with FCE are not receiving the therapy they feel would be most beneficial.

Instead, they primarily only have access to talk therapy. For members of this vulnerable population who do not benefit from talk therapy, we must provide alternative therapy options.

Proposed alternative treatments include art therapy, movement therapy, music therapy, and equine-assisted psychotherapy. All of these therapies incorporate nonverbal elements, so youth who are not comfortable with the verbal focus of talk therapy

may find them more impactful. We have anecdotal evidence that the arts (visual, auditory, and movement) and animal companionship have transformative positive effects on people’s lives and wellbeing. Recent research provides convincing evidence to support that understanding

Art Therapy

Art therapy is an alternative treatment offered across the country by certified art therapists with degrees from accredited graduate programs and supervised clinical experience. 46 In this treatment, patients are led through artmaking processes that can help them communicate and heal trauma more effectively. Research with youth with FCE has indicated that art therapy improves how children in care feel about themselves and helps them develop coping abilities without directly discussing of traumatic life events.47 Art therapy with other populations has been shown to increase behavioral adjustment and reduce hyperactivity among youth with ADHD,48 improve self-esteem,49 support grieving youth,50 and reduce symptoms of depression and PTSD51 – all of which disproportionately affect youth with FCE.

Movement Therapy

Movement therapies such as dance or yoga have also produced success. Dance/movement therapy (DMT), the psychotherapeutic use of movement to promote well-being, is performed by certified DMT therapists who have earned a degree from an approved graduate program and participate in continuing education.52 Research indicates that DMT decreases depression and anxiety and improves interpersonal skills53 and stress management.54 Yoga therapy has been shown to reduce anxiety in youth by replacing the flight-or-fight response with the relaxation response, helping to balance the nervous system. Research also indicates that yoga therapy increases positive coping skills and builds self-esteem.55 Other traumainformed yoga classes have been reported to reduce PTSD symptoms, aid substance use recovery, and improve emotional wellbeing.56 Although few studies have explicitly focused on movement therapies for youth with FCE, the success of these treatments with other populations and the interest from youth57 with FCE warrant further research.

Music Therapy

Music therapy uses clinical music interventions to support patients’ physical, mental, and emotional well-being.58 Music therapists are required to earn a degree from an accredited university, pass a board certification exam, and regularly participate in continuing education.59 Although more rigorous research is needed, particularly as regards youth with FCE, studies so far indicate that music therapy is effective for youth with mental illness.60 Positive outcomes appear most significant for youth with behavioral or developmental disorders.61 Research suggests that music therapy may reduce aggressive and hostile behavior in youth,62 prevent relapses of substance use,63 and help adolescents feel more control over their lives and environment.64 Youth exposed to music therapy reported that it improved their mood, reduced their anxiety, and aided their social interactions.

Equine-Assisted Psychotherapy

Another alternative therapy that has shown promise for youth is equine-assisted psychotherapy. Horses are now used in a range of therapeutic practices, and standardized models and training have been developed for equine-assisted treatments in the last few decades.66 Equine-assisted psychotherapy involves mental health professionals and equine specialists who aid in nurturing the equine-human bond.67 As large prey animals, horses are highly aware of their surroundings and respond to small changes in the patient’s behavior. This provides the patient with immediate feedback about their actions and can be useful in addressing social or emotional concerns.68 Although robust evidence for this relatively new practice currently limited, existing research shows promise.69 For adolescents in residential treatment for emotional and behavioral issues, equine-assisted psychotherapy was associated with greater self-control and self-image and fewer arrests and instances of drug use.70 Studies also indicate that equine-assisted psychotherapy can improve social and behavioral issues71 as well as reduce symptoms of PTSD for youth.

Proposed Solutions and Best Practices

Medicaid Coverage for Alternative Treatments

To ensure equal access to mental health services for youth with FCE, guidance must be produced to support states’ understanding of Medicaid coverage of alternative therapies. Ensuring that there is clarity related to coverage of alternative treatments is critical to increase the participation rates of youth with FCE, improve therapy completion rates, and benefit youth’s mental health and well-being. Art therapy, movement therapy, music therapy, and equine-assisted psychotherapy are among the alternative therapies that show the greatest potential.

We propose a five-year minimum demonstration project that would develop an evidence base for these treatments, establish guidance for states on best practices, and propose braided funding mechanisms to ensure full reimbursement for treatments. This project would allow states and providers time to coordinate on Medicaid funding best practices, thus increasing the availability of covered services and decreasing administrative burdens that act as access barriers. Such an evaluation would also provide evidence-based specific standards for training and ethical guidelines within these treatments for youth with FCE.

Costs

The cost of therapy varies depending on the setting, region, experience level of the therapist, and length and type of session. However, rates for alternative therapies tend to be commensurate with rates for covered talk therapies.The average cost for a single session of talk therapy ranges from $100 to $200, according to a 2019 survey of mental health professionals.73 For individual sessions of art therapy, the American Art Therapy Association estimates average cost to be around $150.74 The cost of a yoga therapy session may range from $85 to $175, according to the International Association of Yoga Therapists, 75 while provider searches suggest that average cost for DMT may hover between $135 and $185.* The average cost of music therapy varies from $80 to $120, based on survey results conducted by the American Music Therapy Association. 76 The average session cost for equine-assisted psychotherapy, which involves both a mental health professional and an equine specialist, is reported by the Equine Assisted Growth and Learning Association to be between $130 and $250.

Equity Considerations

Youth with FCE face significant barriers to accessing alternative treatments and services under Medicaid. However, these alternative therapies are already accessible to individuals who are able to afford out-of-pocket costs.78 Youth with FCE, who are reliant on Medicaid, are denied vital opportunities to get the help they need – opportunities that are accessible to individuals with more resources and wealth. The current state of mental health services in the U.S. is inequitable. Providing guidance to states on Medicaid coverage of alternative services would help shift this disparity.

To achieve this goal, the federal government should fund a five-year minimum demonstration project that will:

1) Develop an evidence base for the success of alternative treatments with youth with FCE,

2) Establish guidance for states, tribes, and territories on best practices to reduce and eliminate access barriers for these treatments, and

3) Propose policies and procedures to support braided funding mechanisms and billing codes through Medicaid and Title IV-E to ensure full reimbursement of the actual cost of covered therapies for foster youth.

Please contact Angelique Day, Ph.D. ([email protected]) or Emma Buckland Young ([email protected]) with questions or concerns about this research.

This figure was estimated using a state-by-state search of registered or certified dance/movement therapists. From each of five affordability brackets (as determined by the U.S. News & World Report), the two states with the greatest number of foster youth were selected (as determined by The Imprint). Two to six therapists who reported their prices for individual sessions were selected from each state. For therapists who reported a range, the average (rounded up) was recorded. The prices were averaged for each state. All state prices were then averaged together. The range reported here is that final average of all states +/- one standard deviation, rounded to the nearest $5. U.S. News & World Report. (n.d.). Affordability. Retrieved March 1, 2023 from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/opportunity/affordability The Imprint. (2022). Youth in care: 2011-2022. Who Cares: A National Count of Foster Homes and Families. Retrieved March 1, 2023 from https://www.fostercarecapacity.com/data/youth-in-care

References:

1.Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). (2022). Trends in foster care and adoption: FY 2012 – 2021. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/trends-foster-careadoption; Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). (2022). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2021 Estimates. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau.

2 National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019, November 1). Mental health and foster care. https://www.ncsl.org/research/humanservices/mental-health-and-foster-care.aspx

3.Bullinger, L. R., & Meinhofer, A. (2021). The Affordable Care Act increased Medicaid coverage among former foster youth: Study examines the Affordable Care Act effect on Medicaid coverage among former foster youth. Health Affairs, 40(9), 1430–1439. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00073

4.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:Center for Healthy Children. 5 National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019, November 1). Mental health and foster care.https://www.ncsl.org/research/humanservices/mental-health-and-foster-care.aspx

5.National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019, November 1). Mental health and foster care.

6.Casey Family Programs. (2004). Assessing the effects of foster care: Mental health outcomes from the Casey National Alumni Study.

http://www.casey.org/media/AlumniStudy_

US_Report_MentalHealth.pdf

7.Pecora, P. J., Jensen, P. S., Romanelli, L. H., Jackson, L. J., & Ortiz, A. (2009). Mental health services for children placed in foster care: An overview of current challenges. Child Welfare, 88(1), 5–26.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19653451/

8.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children; Szilagyi, M. A., Rosen, D. S., Rubin, D., Zlotnik, S., Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, Committee on Adolescence, & Council on Early Childhood. (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics, 136(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2656

9.Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). (2022). The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2021 Estimates. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau.

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents

/cb/afcars-report-29.pdf

10.Szilagyi, M. A., Rosen, D. S., Rubin, D., Zlotnik, S., Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, Committee on Adolescence, & Council on Early Childhood. (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics, 136(4).

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2656; Trivedi, S. (2019). The Harm of Child Removal. New York University Review of Law & Social Change, 43, 523- 580. https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/1085/

11.Fisher, P. A., Mannering, A. M., Van Scoyoc, A., & Graham, A. M. (2013). A translational neuroscience perspective on the importance of

reducing placement instability among foster children. Child Welfare, 92(5), 9–36.

12.Spencer, J. W., & Knudsen, D. D. (1992). Out-ofhome maltreatment: An analysis of risk in various settings for children. Children and Youth Services Review, 14(6), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/0190-7409(92)90002-D; Fowler, D., & Ryan, K. (2020). M.D. ex rel

Stukenberg v. Abbott, No. 2:11-cv-84. First Court Monitors’ Report 2020. Retrieved from: https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/cd

71f14e349d1133df3072ebc25c9350/Texas%20child%20welfar

e%20monitors%20report%20June%202020.pdf; Ortega, B. (2017, June 4). A horrifying journey through Arizona foster care, and why we don’t know

how many more children may be abused. The Arizona Republic.

https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local

/arizonainvestigations/2017/06/04/arizona-foster-care-childabuse/362836001/;Abramo, A. (2018, October 17). Report: Washington foster kids abused at out-of-state group home. Crosscut. https://crosscut.com/news/2018/10/reportwashington-foster-kids-abused-out-state-group-home

13.National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019,November 1). Mental health and foster care.

https://www.ncsl.org/research/humanservices/mental-health-and-foster-care.aspx

14.Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Table 8.8 PE – 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed

Tables. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-detailed-tables

15.Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. (2020). Table 8.7 PE – 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed

Tables. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020- nsduh-detailed-tables

16.6 Kessler, R. C., Heeringa, S., Lakoma, M. D., Petukhova, M., Rupp, A. E., Schoenbaum, M., Wang, P. S., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2008). Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity

Survey Replication. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(6), 703–711. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126

17. National Coalition for the Homeless. (2009). Mental Illness and Homelessness. https://www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/Mental_

Illness.pdf; Winiarski, D. A., Rufa, A. K., Bounds, D. T., Glover, A. C., Hill, K. A., & Karnik, N. S. (2020). Assessing and treating complex mental health needs among homeless youth in a shelter-based clinic. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 109.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4953-9

18.Dupéré, V., Dion, E., Nault-Brière, F., Archambault, I., Leventhal, T., & Lesage, A. (2018). Revisiting the link between depression symptoms and high school dropout: Timing of exposure matters. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(2), 205–211.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.09.024

19.Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/repor

ts/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/202

0NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

20. Development Services Group, Inc. (2017). Intersection Between Mental Health and the Juvenile

Justice System. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

https://www.ojjdp.gov/mpg/litreviews/IntersectionMental-Health-Juvenile-Justice.pdf; Erickson, C. D. (2012). Using systems of care to reduce incarceration of youth with serious mental illness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(3-4), 404– 416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9484-4

21.United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2016). Ending Chronic

Homelessness in 2017. https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_librar y/Ending_Chronic_Homelessness_in_2017.pdf; National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Trends in high school dropout and completion rates in the United States. Institute of Education Sciences.

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/dropout/intro.asp; Health Policy Institute. (n.d.). Substance abuse: Facing the costs. Georgetown University.

https://hpi.georgetown.edu/abuse/; O’Neill Hayes, T. (2020, July 16). The economic costs of the U.S. criminal justice system. American Action Forum. https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/theeconomic-costs-of-the-u-s-criminal-justice-system/

22.Snowden, L. R., Cordell, K., & Bui, J. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in health status and community functioning among persons with untreated mental illness. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01397-1

23.National Conference of State Legislatures. (2021, January 26). Disproportionality and race equity in

child welfare. https://www.ncsl.org/humanservices/disproportionality-and-race-equity-in-childwelfare; Raimon, M.L., Weber, K., & Esenstad, A. (2015). Better outcomes for older youth of color in foster care. Center for the Study of Social Policy.

https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/BetterOutcomes-for-Older-Youth-of-Color-in-FosterCare.pdf

24.Bullinger, L. R., & Meinhofer, A. (2021). The Affordable Care Act increased Medicaid coverage among former foster youth: Study examines the Affordable Care Act effect on Medicaid coverage among former foster youth. Health Affairs, 40(9), 1430–1439.

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00073

25.Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2022, January). Health-care coverage for children and youth in foster care-and after. U.S Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau.

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/issuebriefs/health-care-foster/

https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/USACF

CWIG/2022/12/19/file_attachments/2359168/formerfoster-care-coverage-changes.pdf

26.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children.

27.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children; Bernstein, L. (2022, March 6). This is why it’s so hard to find mental health counseling right now. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2022/03/06/therapist-covid-burnout/

28.Gottlieb, J. (2021, July 12). The cost of administrative burdens: Providers stop accepting Medicaid due to hassle, lost payments. Harris School of Public Policy, The University of Chicago. https://harris.uchicago.edu/news-events/news/costadministrative-burdens-providers-stop-acceptingmedicaid-due-hassle-lost; Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration: Center for Healthy Children; Tiede, L., & Rosinksy, K. (2019). Funding supports and services for young people transitioning from foster care. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/wpcontent/uploads

/2019/09/YVReport_ChildTrends_Sept2019.pdf

29.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children.

30.Personal communication from J. Simpson to E. Buckland Young on April 17, 2023; Personal communication from T. Kirby to E. Buckland Young

on February 6, 2023.

31.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children; Pecora, P. J., Jensen, P. S., Romanelli, L. H., Jackson, L. J., & Ortiz, A. (2009). Mental health services for children placed in foster care: An overview of current challenges. Child

Welfare, 88(1), 5–26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19653451/

32.National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019, November 1). Mental health and foster care. https://www.ncsl.org/research/humanservices/mental-health-and-foster-care.aspx

33.McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2014). Childhood adversity and neural development: deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012

34.Wilkie, K. D., Germain, S., & Theule, J. (2016). Evaluating the efficacy of equine therapy among atrisk youth: A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös, 29(3), 377– 393.https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2016.1189747

35.Hambrick, E. P., Oppenheim-Weller, S., N’zi, A.M., & Taussig, H. N. (2016). Mental health interventions for children in foster care: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 65– 77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.002

36.Cantos, A. L., & Gries, L. T. (2010). Therapy Outcome with Children in Foster Care: A Longitudinal Study. Child & Adolescent Social Work

Journal, 27(2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-010-0198-5

37.National Foster Youth Institute. (2021, August 18). Listening Session.

38.Barrett, M. S., Chua, W.-J., Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B., & Thompson, D. (2008). Early withdrawal from withdrawal from mental health treatment: Implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy, 45(2), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.247

39.Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. W. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(3), 148– 153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005

40.Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. W. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(3), 148– 153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005; Anda, R.F., Felitti, V.J., Bremner, J.D., Walker, J.D.,

Whitfield, C., Perry, B.D., Dube, S.R., & Giles, W.H. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4; Solomon, E. P., & Heide, K. M. (2005). The biology of trauma: Implications for treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(1), 51–60.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504268119

41.1 National Foster Youth Institute. (2021, August 18). Listening Session.

42.National Foster Youth Institute. (2021, August 18). Listening Session

43.National Foster Youth Institute. (2021, August 18). Listening Session

44.Nsonwu, M. B., Dennison, S., & Long, J. (2015). Foster care chronicles: Use of the arts for teens aging out of the foster care system. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 10(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2014.935546

45.Lougheed, S. C., & Coholic, D. A. (2018). ArtsBased Mindfulness Group Work with Youth Aging Out of Foster Care. Social Work with Groups, 41(1-2), 165-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2016.1258626; Morrison, M. L. (2007). Health benefits of animalassisted interventions. Complementary Health Practice Review, 12(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533210107302397; Hanna, J. L. (2006). Dancing for health: conquering and preventing stress. AltaMira Press

46.7 Coholic, D., Lougheed, S., & Cadell, S. (2009). Exploring the helpfulness of arts-based methods with children living in foster care. Traumatology, 15(3), 64-71.https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765609341590

47.Coholic, D., Lougheed, S., & Cadell, S. (2009). Exploring the helpfulness of arts-based methods with children living in foster care. Traumatology, 15(3), 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765609341590

48.8 Lee, S.-L., & Liu, H.-L. A. (2016). A pilot study of art therapy for children with special educational needs in Hong Kong. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 51, 24–29.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.08.005; Henley, D. (1998). Art therapy in a socialization program for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Art Therapy, 37(1), 2–12.

49.Hartz, L., & Thick, L. (2005). Art therapy strategies to raise self-esteem in female juvenile offenders: A comparison of art psychotherapy and art as therapy approaches. Art Therapy, 22(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129440

50.Dye, M. (2018). Evaluating the benefits of art therapy interventions with grieving children [Unpublished graduate thesis]. James Madison

University. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/edspec201019/129

51.Campbell, M., Decker, K. P., Kruk, K., & Deaver, S. P. (2016). Art therapy and cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy, 33(4), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1226643; Chapman, L., Morabito, D., Ladakakos, C., Schreier, H., & Knudson, M. M. (2001). The effectiveness of art therapy interventions in reducing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in pediatric trauma atients. Art Therapy, 18(2), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2001.10129750 Lyshak-Stelzer, F., Singer, P., Patricia, S. J., & Chemtob, C. M. (2007). Art therapy for adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Art Therapy, 24(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129474; Ugurlu, N., Akca, L., & Acarturk, C. (2016). An art therapy intervention for symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 11(2), 89–102.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2016.1181288

52.American Dance Therapy Association. (n.d.). Become a dance movement therapist. https://www.adta.org/become-a-dance-movementtherapist

53.Koch, S. C., Riege, R. F. F., Tisborn, K., Biondo, J., Martin, L., & Beelmann, A. (2019). Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis update. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1806. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806

54.Brauninger, I. (2012). Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: A randomized controlled trial (RCT). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(5), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.07.002

55.Williams-Orlando, C. (2013). Yoga therapy for anxiety: a case report. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine, 27(4), 18-21.

56.Tibbitts, D. C., Aicher, S. A., Sugg, J., Handloser, K., Eisman, L., Booth, L. D., & Bradley, R. D. (2021). Program evaluation of trauma-informed yoga for vulnerable populations. Evaluation and Program Planning, 88, 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.101946; Smoyer, A. B. (2016). Being on the mat: A process evaluation of trauma-informed yoga for women with substance use disorders. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 43(4), 61–84; van der Kolk, B. A., Stone, L., West, J., Rhodes, A., Emerson, D., Suvak, M., & Spinazzola, J. (2014). Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(6), e559–e565. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13m08561

57.7 National Foster Youth Institute. (2021, August 18). Listening Session.

58.American Music Therapy Association. (n.d.). What is music therapy? https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/

59.American Music Therapy Association. (n.d.). Professional Requirements for Music Therapists.

https://www.musictherapy.org/about/requirements/; Certification Board for Music Therapists. (n.d.).

Board Certification. https://www.cbmt.org/candidates/certification/

60.Gold, C., Voracek, M., & Wigram, T. (2004). Effects of music therapy for children and adolescents with psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00298.x

61.Montello, L., & Coons, E. E. (1998). Effects of active versus passive group music therapy on preadolescents with emotional, learning, and behavioral disorders. The Journal of Music Therapy, 35(1), 49–67.https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/35.1.49

62.James, M.R. (1990). Adolescent values clarification: A positive influence on perceived locus of control. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 35(2), 75–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45091703

63.James, M.R. (1990). Adolescent values clarification: A positive influence on perceived locus of control. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 35(2), 75–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45091703

64.James, M.R. (1990). Adolescent values clarification: A positive influence on perceived locus of control. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 35(2), 75–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45091703

65.Preyde, M., Berends, A., Parehk, S., & Heintzman, J. (2017). Adolescents’ evaluation of music therapy in an inpatient psychiatric unit: A quality improvement project. Music Therapy Perspectives, 35(1), 58–62.https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miv008

66.Buck, P. W., Bean, N., & De Marco, K. (2017). Equine-assisted psychotherapy: An emerging traumainformed intervention. Advances in Social Work, 18(1), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.18060/21310

67.Equine Assisted Growth and Learning Association. (n.d.). Eagala. https://www.eagala.org/index

68.Buck, P. W., Bean, N., & De Marco, K. (2017). Equine-assisted psychotherapy: An emerging traumainformed intervention. Advances in Social Work, 18(1), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.18060/21310

69.Wilkie, K. D., Germain, S., & Theule, J. (2016). Evaluating the efficacy of equine therapy among atrisk youth: A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös, 29(3), 377– 393. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2016.1189747

70.Bachi, K., Terkel, J., & Teichman, M. (2012). Equine-facilitated psychotherapy for at-risk adolescents: The influence on self-image, self-control and trust. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104511404177

71.Buck, P. W., Bean, N., & De Marco, K. (2017). Equine-assisted psychotherapy: An emerging traumainformed intervention. Advances in Social Work, 18(1), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.18060/21310

72.McCullough, L., Risley-Curtiss, C., & Rorke, J. (2015). Equine facilitated psychotherapy: A pilot study of effect on posttraumatic stress symptoms in maltreated youth. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 14(2), 158–173.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2015.1021658

73.Lauretta, A. (2022, November 15). How much does therapy cost? Forbes Health. https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/how-muchdoes-therapy-cost/

74.Personal communication from T. Kirby to E. Buckland Young on February 27, 2023.

75.Personal communication from B. Whitney-Teeple to E. Buckland Young on February 22, 2023.

76.American Music Therapy Association. (2021). Workforce Analysis.

77.Personal communication from A. Blossom to E. Buckland Young on March 1, 2023.

78.Herd, T., Palmer, L., Font, S. (2022). The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth Exposed to Maltreatment. Research-to-Policy Collaboration:

Center for Healthy Children.